The transition towards climate neutrality is creating both winners and losers. Renewable energy development often faces opposition from local communities concerned about potential environmental impacts without significant economic benefits. Using Italy as a case study, this column investigates whether such opposition translates into political costs at the polls. It finds that local governments authorizing wind turbines do not face electoral penalties. On the contrary, the development of wind plants has a favorable impact on electoral outcomes when the incumbent administration is more climate friendly.

The revised Renewable Energy Directive EU/2023/2413 raises the EU’s target of renewables share in EU energy consumption for 2030 to a minimum 42.5%, up from the previous 32% target. The share stood at 23% in 2022. In Italy, the greatest effort in terms of renewable investment concerns the wind energy sector. In 2022, only 17% of renewable capacity came from wind energy, less than half the average of the EU (Eurostat). According to the revised national target, the total capacity installed in wind energy plants will need to reach 28.1 gigawatts by 2030, requiring an average of 2 gigawatts per year to be newly installed between 2023 and 2030, about five times as much as the amount installed during 2017–22. The sheer size of investment required in wind plants coupled with the potentially significant looming trade-offs given the country’s cultural heritage, high tourism penetration, and degree of urbanisation make Italy an exceptionally interesting case study.

Renewables: Local costs versus diffuse benefits

The trade-offs entailed by the transition towards climate neutrality have sparked widespread discussions among economists and the general public. The development of renewables gives rise to global gains potentially matched by local costs (Juhász and Lane 2024). For instance, Dröes and Koster (2020) detect a negative impact of the development of wind turbines and solar farms on house prices in the Netherlands, while Fabra et al. (2022) show that renewable plants do not increase local jobs. Additional costs refer to local identity and heritage preservation (Carattini et al. 2022). The incentives for local government to adopt a climate-progressive agenda diminish where local adverse consequences translate into electoral choices.

Wind turbines and local electoral choices

We investigate the existence of electoral backlash on incumbent regional governments from the development of wind turbines in Italy (Daniele et al. 2024). Outside Europe, a substantial body of literature has examined the impact of wind power plants on electoral outcomes (Bayulgen et al. 2021, Stokes 2016, Urpelainen and Tianbo Zhang 2022). To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence on the impact in European countries and on local elections. The latter is surprising, given that local governments are both crucial in the permitting process and the most interested in reducing any local costs caused by turbine construction.

We use municipal data on regional election outcomes matched with information on the development of wind turbines during 2005–2020. Wind energy capacity went from less than a gigawatt in 2005 to nearly 10 gigawatt in 2020. The diffusion of wind turbine development reflects the uneven geographical availability of natural resources: each year during 2005–2020, around 4% of southern municipalities have seen the development of brand-new wind turbines, as opposed to 0.3% of municipalities located in the Centre-North. We thus focus on those regions where renewables investment has been most intense, i.e. Southern regions (with the exception of Sicily and Sardinia, for which data on electoral outcomes are not available), spanning approximately 1,700 municipalities. Furthermore, we focus on elections of the layer of government that is directly in charge of permit-granting procedures, the Regioni.

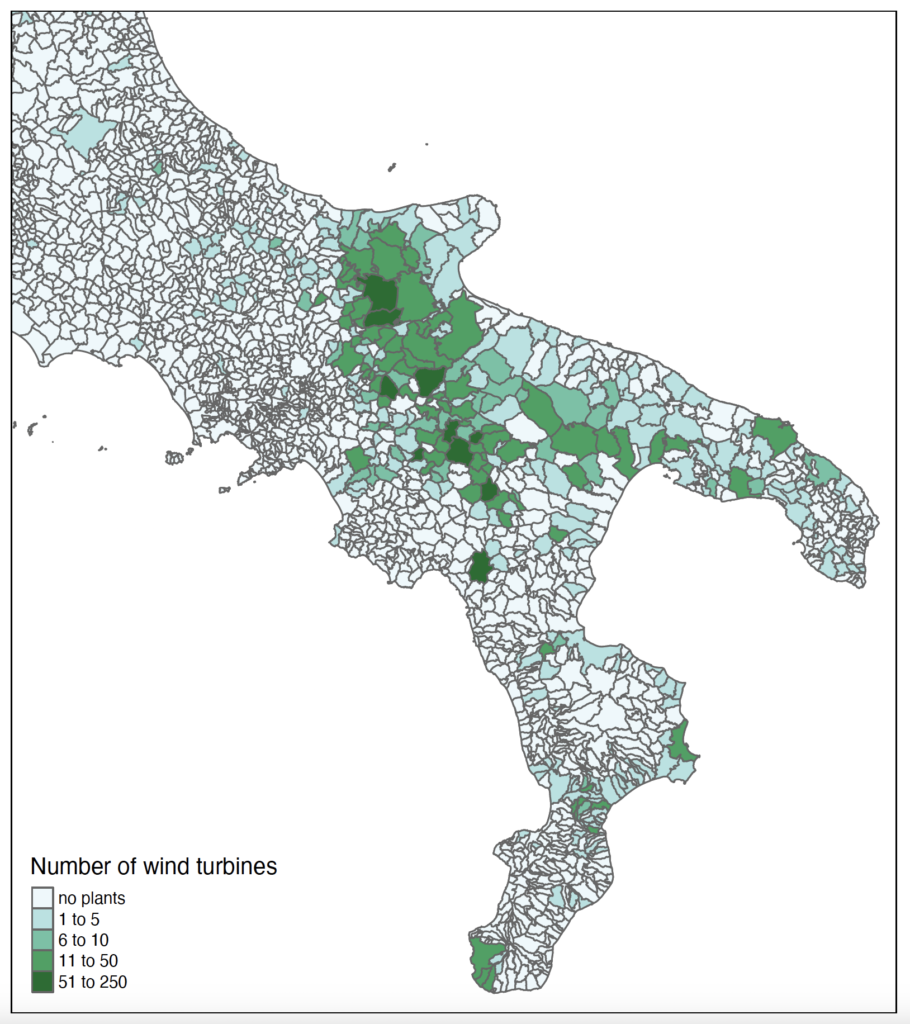

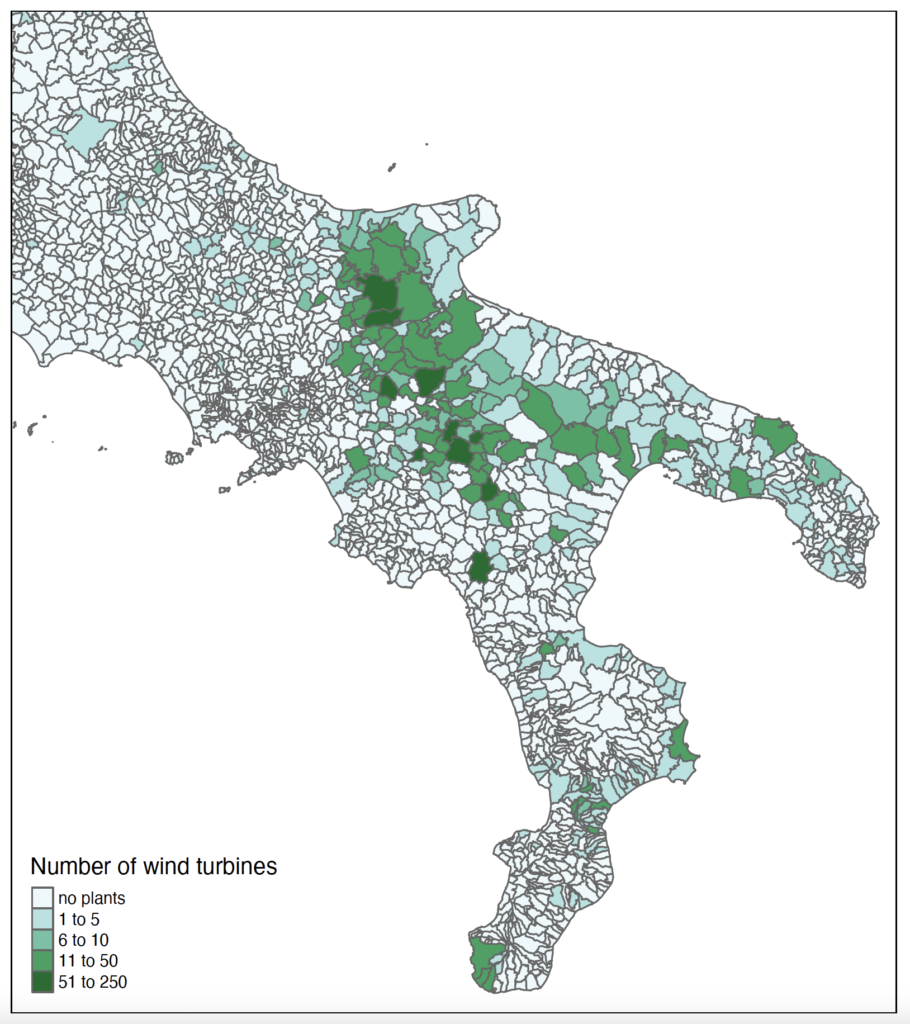

Figure 1 Number of plants installed in Italian municipalities during 2005–2020

Notes: The municipalities in Sicily and Sardinia are excluded from the sample since data on electoral outcomes are missing for these two regions. Only subsidised wind turbines are included.

Source: Gestore Servizi Energetici S.p.A.

Empirical strategy

We compare the voting share won by the incumbent regional government in municipalities where at least one wind turbine was built during the previous mandate with the share won in municipalities in the same region and voting in the same year where no development occurred. We control for a large set of socioeconomic and geographic municipal characteristics that might influence both the development of wind turbines and electoral preferences.

Yet, even accounting for those, the timing and location of wind turbine development are unlikely exogenous. For example, the incumbent coalition might experience a fall in popularity in a given municipality and decide to support/oppose the installation of wind turbines in order to gain the votes of supporters/opponents. To address the potential endogeneity in our specification, we rely on an instrument widely used in this literature, the average wind speed.

Please, in my backyard

Our findings rule out the existence of electoral costs associated with wind turbine development. On the contrary, incumbent administrations with a pro-renewables stance tend to enjoy increased electoral support as wind turbines are developed. The reward is lower in municipalities characterised by higher tourism or real estate prices. This might be explained by the (real or perceived) negative impact of wind turbines on local attractiveness and the housing market.

In summary, our results suggest that concerns over potential electoral penalties should not deter governments from implementing policies aiming at accelerating the energy transition in their regions.

Source: cepr.org