The future of work and the future of poverty are closely bound up with each other.

Global value chains, those webs of firms criss-crossing the world that collectively bring products to market, have driven economic growth since the 1980s. According to the World Bank, they have enabled many countries in the Global South to transition from low-income to middle-income status within the past few decades.

For example, 100% of South Asian countries were categorised as low-income in 1987. In 2023, it was just 13%. The rest had transitioned to a higher status. As of 2024, the World Bank defines middle-income countries as those with a gross national income per capita between $1,136 and $13,845.

Statistics like these have led to a strong belief within much of the development industry that global value chains offer companies and countries the prospect of “upgrading”. Once integrated into them, it becomes possible for firms to improve efficiency, move towards producing higher value-added products, and shift to higher positions in the global value chain hierarchy.

By extension, global value chains also open up opportunities for “social upgrading”. Alongside economic growth, improvements in employment, remuneration, workers’ rights, and workplace safety are all possible. To their proponents, economic growth fuelled by integration into global value chains is nothing less than a rising tide that lifts all boats.

There’s just one small problem. This scenario has, with few exceptions, failed to materialise. The new wealth has been so unequally distributed that middle-income countries are still home to 70% of the world’s poor. The fact is, workers in these countries continue to capture little of the value they create. As long as work remains structured as it is, many cannot do more than toil to maintain their poverty.

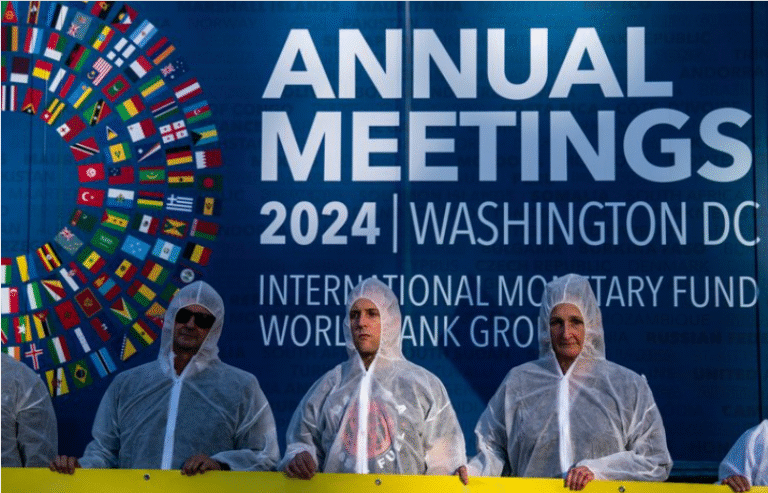

The latest World Development Report suggests that even the World Bank is beginning to understand this. Sounding a note of warning about the economic state of middle-income countries, the report says the upward trend of eradicating poverty is coming to an end. Economic growth in middle-income countries is slowing down every decade, and income levels are not catching up with those in advanced economies.

The World Bank renders the “middle-income trap” a technical problem, when it is in fact deeply political

But while the report acknowledges many real and worrying problems, it continues to ignore the elephant in the room. Power relations between the Global North and Global South are deeply unequal, and the Global North uses that inequality to its punishing advantage.

By omitting this dynamic, the World Bank renders the “middle-income trap” a technical problem, when it is in fact deeply political. And technical solutions can’t solve political problems.

The ‘technical’ issue

The problem, according to the report, is the development strategies that worked well for low-income countries yield diminishing returns after the transition to middle-income status.

These initial strategies typically focus on attracting foreign direct investment. But middle-income countries’ biggest need is to boost the sophistication of their economic structures. Without this, many countries find themselves unable to move beyond the middle-income tier that investment-centred development strategies had propelled them to.

In and of itself, this diagnosis is not particularly controversial. Critical scholars in development studies have long questioned neoliberal claims that participation in global value chains alone is enough to guarantee prosperity. But it’s not this belated acknowledgement that is so interesting. It’s what the report continues to hide from view, and how it pulls off that disappearing trick so well.

“To achieve more sophisticated economies, middle-income countries need two successive transitions, not one,” the report tells us. First, the investments that enabled the transition to middle-income status need to be coupled with “infusion”. This means policies that deliberately encourage the spread of new knowledge and cutting-edge technology across the economy.

As middle-income countries run out of new technologies to infuse, they must then transition again to driving innovation. Flows of physical and financial capital must be complemented by human capital, which is achieved by offering “the conditions cherished by innovators”. According to the report, these are freer economies, human rights, and liveable cities.

The report further advises middle-income countries to calibrate their mix of the three i’s – investment, infusion, and innovation. Actors not driving economic change must be disciplined. Creativity must be rewarded. Outdated policies and institutions must be removed. Finally, markets must be made globally contestable through “openness to foreign investors and global value chains”, so that domestic firms can access the markets, technology, and know-how that will allow them to add value and grow.

It all sounds very technical – which is exactly where the point gets missed. Achieving these transitions is not simply a matter of following the World Bank’s playbook correctly. It’s a matter of politics. Particularly, it’s a matter of how countries in the Global North leverage unequal power relations to prevent these transitions from taking place.

This techno-politics occludes very significant aspects of the position that middle-income countries in the Global South occupy in the world economy

Tania Murray Li, an anthropologist who has laboured on the frontlines of critical development research since the late 1990s, writes in her book The Will to Improve that development interventions are predicated upon “rendering technical”. This, she argues, simultaneously renders the issue non-political by removing power relations from the equation. “Antipolitics of this kind is subliminal and routine,” Li writes. “Experts are trained to frame problems in technical terms.”

This is exactly what the experts penning this year’s World Development Report have done. Seemingly, the “middle income trap” is something that happens when a state forgets to encourage infusion or drive innovation. A kind of macroeconomic oopsie that can be rectified by simply remembering what to do.

This is techno-politics, to borrow a term from the political theorist and historian Timothy Mitchell. And this techno-politics occludes very significant aspects of the position that middle-income countries in the Global South occupy in the world economy.

Global inequality at its heart

The transformations that brought about the rise of middle-income countries were part of a larger restructuring of geoeconomic power relations that began in the late Cold War era. Transnational corporations began to relocate their manufacturing operations outside the Global North, both to escape the power of organised workers and to tap into the vast reservoirs of cheap, unorganised labour on the world’s economic periphery.

At the same time, in the context of the international debt crisis of the 1980s, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank enforced structural adjustment programmes on many countries. These compelled governing elites in the Global South to deregulate their economies and open up to investments from abroad.

These steps laid the foundation for the global value chain system that has emerged since the end of the Cold War. Rather than being integrated within national spaces, different parts of the production process are dispersed across the globe under the coordination of transnational corporations.

It is through their integration into these value chains – predominantly at the point of manufacturing, but also through raw material extraction and business process outsourcing – that many countries in the Global South made their transition from low-income to middle-income status. It is also in this context that their growth trajectories are currently decelerating.

The power to prevent progress

The above is one level of understanding for why our global economy is currently structured the way it is. But if we layer power relations onto this history of development, an altogether different understanding emerges.

The developmental constraints many middle-income countries face are not rooted in technical policy issues. Instead, global value chains have entrenched capital’s inordinate power over labour, which, as Benjamin Selwyn has argued, has enabled the super-exploitation of workers and the suppression of further developmental transformations.

The companies at the head of these chains profit from this arrangement and use their immense power to maintain the status quo. Politicians in the Global North use their own power to reinforce these companies’ advantage, as they are ultimately bringing cheap goods and services to their home populations.

These companies have wilfully created a massive population of working poor across the region and are doing their utmost to keep it that way

In East Asia, which is home to more than 32% of the total global workforce, Dae-oup Chang has shown how companies’ business practices actively prevent upward convergence of labour standards and welfare across the region. They do this by exerting considerable influence over the laws and regulations shaping labour regimes across the region, above all ensuring that wages are kept low, working hours long, and employment insecure.

As a result, these companies have wilfully created a massive population of working poor across the region and are doing their utmost to keep it that way. “Many workers in neoliberal sweatshops are de facto informal workers who have little institutional protection for the security of their jobs and livelihoods,” Chang writes. This is compounded by the fact that transnational corporations also exert their power to ensure favourable tax policies, effectively depriving states of the revenues needed to fund substantial welfare and social protection.

The key point here is this: the value chains that enable transnational corporations to leverage their power over labour to maximise profits do not seek to do anything else but that. They have no social goal – quite the opposite – and thus are incapable of delivering anything other than diminished forms of industrialisation, centred on gains in productivity and export growth. As the economist Andy Sumner has shown, such industrial growth trajectories are generally characterised by falling labour shares of income, weak employment growth, and an expanding informal sector.

The deepening of within-country inequality that results from these dynamics is the key reason that world poverty is concentrated in middle-income countries in the Global South.

The real key to development is shifting power

The techno-politics underpinning the 2024 World Development Report make no attempt to address these asymmetrical power relations. Instead, it’s the report’s authors effectively conceal them through their narrative choices and policy prescriptions.

Any pathway to escaping the ‘middle-income trap’ must support working classes to navigate their way out of precarity, for that itself is a major part of the trap. To do that, it must challenge the power relations underlying global value chains. Hardly an easy path, but that’s the path nonetheless. Such a politics would aim to make gains for labour through radical structural reforms, against the determined opposition of those profiting from super-exploitation.

These gains will have to be made on multiple fronts. Drawing on Nicola Philip’s useful delineation of forms of power in the contemporary global economy, a successful class struggle from below would have to confront a number of asymmetries. These include:

- the asymmetries of market power that allow global capital to determine what will be produced where and on what terms;

- the asymmetries of social power that let transnational corporations engage in global labour arbitrage;

- and the asymmetries of political power that enable corporate forces to shape economic policy regimes in accordance with their own interests.

This will entail thinking anew about how to organise and mobilise working classes in a world where capital has been winning the class struggle for far too long. It will entail leveraging the links binding workers’ struggles to the mass protests that have become a near permanent fixture of political landscapes in the Global South. And it will entail extending the class struggle beyond formal workers to the surplus populations relegated to wageless life by the vagaries of neoliberal capitalism.

In addressing these challenges, trade unions and the social movements of working classes will most likely shapeshift – they won’t look like the unions and movements we came to know during the second half of the twentieth century. In the political arena, new workers’ parties must be formed and must work in tandem with unions and movements to advance radical structural reforms that shifts power decisively in favour of labour over capital.

As Andre Gorz once put it, such reforms “are to be regarded as a means and not an end, as dynamic phases in a progressive struggle, not as stopping places”. And precisely because the relationship between capital and labour is so profoundly globalised, the structures of solidarity must also defy the territorial borders of nation-states.

These are daunting tasks, but anything less than this is tantamount to capitulating to a future of endless precarity, which is no future at all. Indeed, if there is to be a future which is not a dystopia of exploitation, it is class struggle that will carve the path towards it. Not the techno-politics offered to us by the World Bank and its ilk.

Source: opendemocracy.net