The shift from fossil fuels to renewable technologies may render the global economy less oil-intensive and more metals-intensive. This column examines how metals supply shocks propagate through production networks and impact inflation. It finds that copper supply shocks have significant and persistent effects on both headline and core inflation. In comparison, oil supply shocks mostly impact headline inflation immediately. As the global economy becomes more metals-intensive, central banks need to be aware that the effect of metals price shocks on inflation could be less visible initially but more persistent.

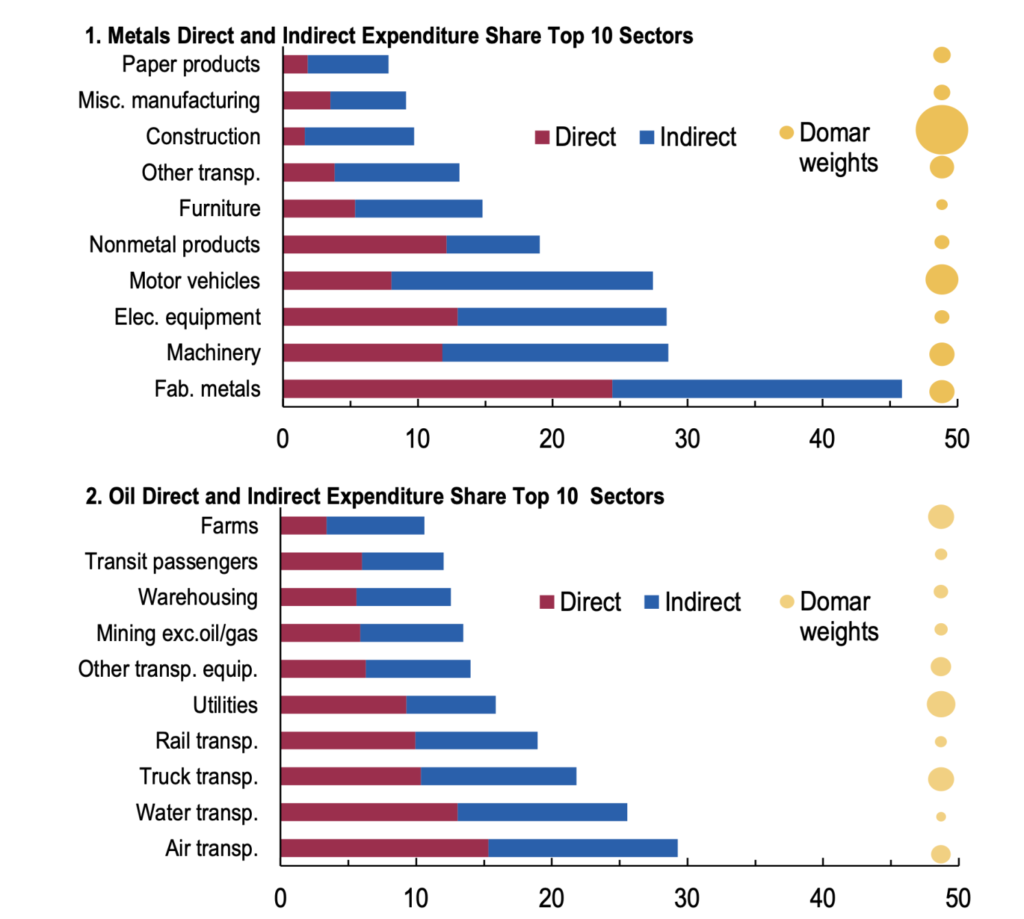

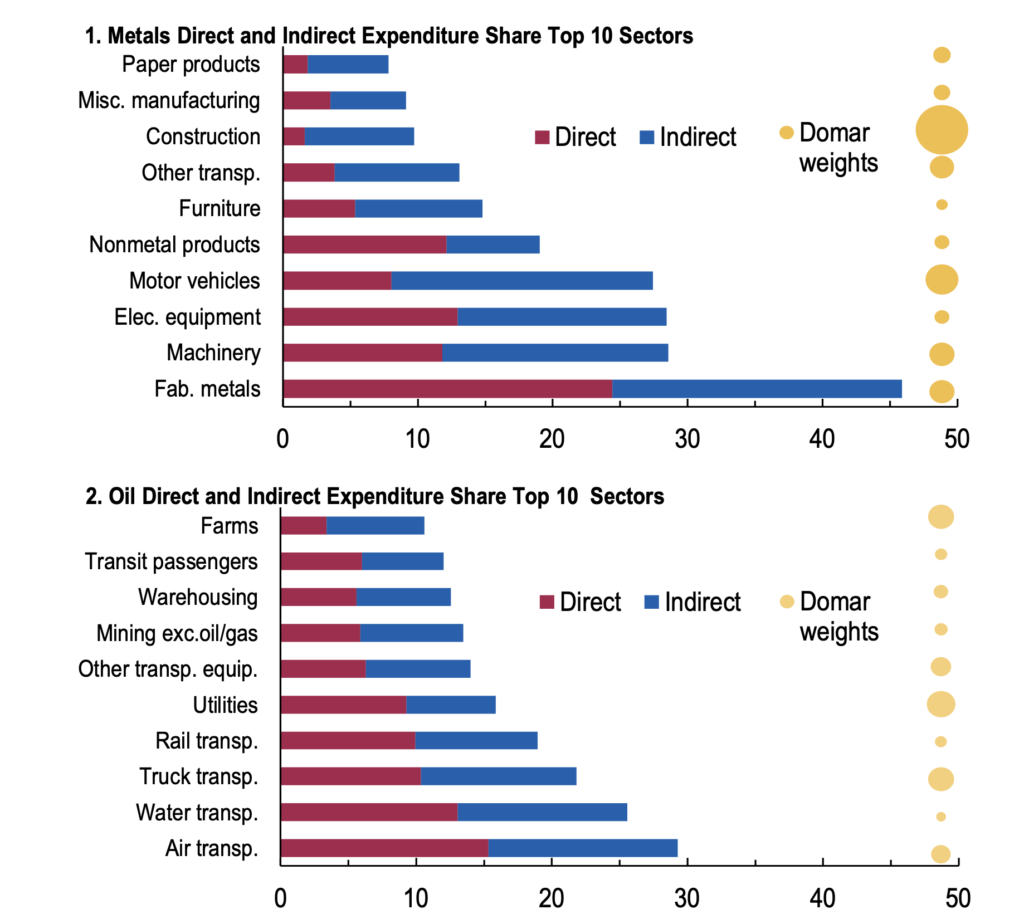

Metals matter for inflation. Even though metals represent only a small fraction of final consumption expenditures (for example, metals represent 0.01% of final consumption expenditure compared to 2.6% for oil and coal products in the US), they account for over 10% of direct input expenditure in sectors like electrical equipment and machinery. Using information on input-output linkages, we observe that metals are not only direct inputs but also serve as indirect inputs across various sectors. For example, the expenditure shares of metals in gross output of the fabricated metals, machinery, and electrical equipment sectors are 46%, 28%, and 27%, respectively (Figure 1).

In the construction sector, indirect exposure to base metals is four times larger than direct exposure – a consideration even more important in light of the high Domar weight of the construction sector in the US economy. In contrast, oil products are primarily used as fuel for energy production in transportation and utilities, resulting in a less significant indirect exposure compared to metals. This difference in how metals and oil enter the production network suggests that metal price shocks could have a more persistent impact on inflation, especially core inflation, while oil price shocks are likely to affect headline inflation in a more instant way.

Figure 1 Intermediate input expenditure share of metals and oil in gross output in the US (top ten sectors)

Note: The direct expenditure share is defined as the sectoral intermediate input expenditure of metals (oil) as a share of sectoral gross output. The indirect expenditure share is the Leontief inverse share element minus the direct expenditure share. The Domar weight is the ratio of the nominal value of each industry’s gross output to GDP. Construction shows the highest Domar Weight (9.59%) and the water transportation sector the lowest (0.03%). We define the metals sector as the sum of the non-oil and non-gas mining sector and the primary metal sector. The oil sector is the sum of the mining of oil and gas sector and the petroleum and coal products manufacturing sector.

Commodity price shock

We start by estimating the effects of copper price shocks on inflation using instrumental variable (IV) local projections (LP) methods (Jordà 2005). To correct for the potential endogeneity in metals and oil prices, we use commodity price shocks identified in the literature as instruments for commodity prices (Stuermer 2018, Jacks and Stuermer 2020, Boer et al. 2024, Baumeister et al. 2024). We use copper supply shocks from Baumeister et al. (2024) and oil supply shocks are sourced from Baumeister and Hamilton (2019). The regression is estimated using monthly data from 1996:m2 to 2019:m12, for a balanced panel with 39 countries.

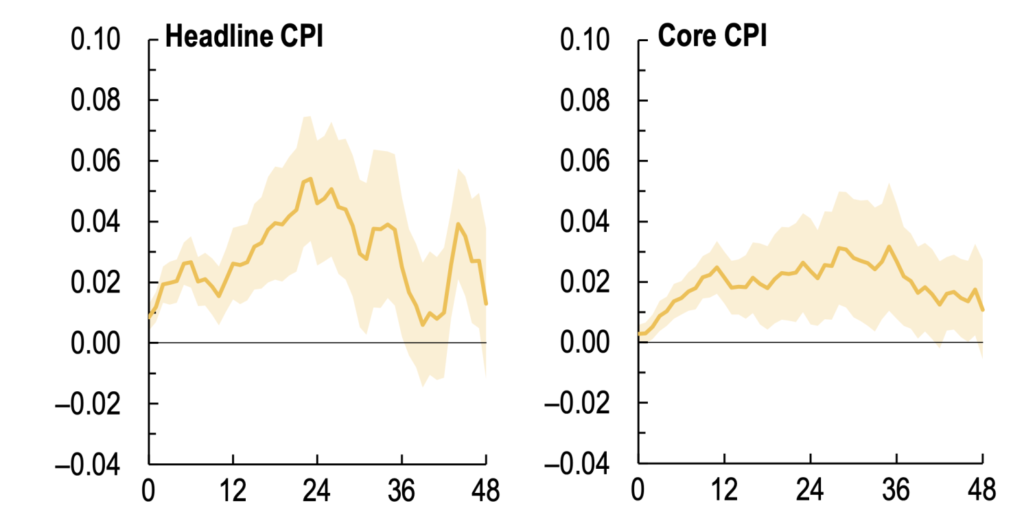

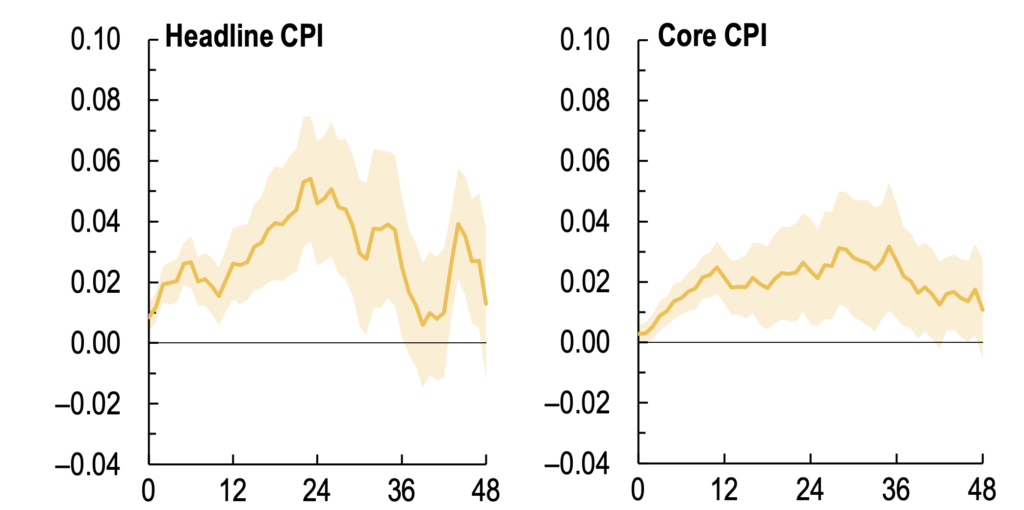

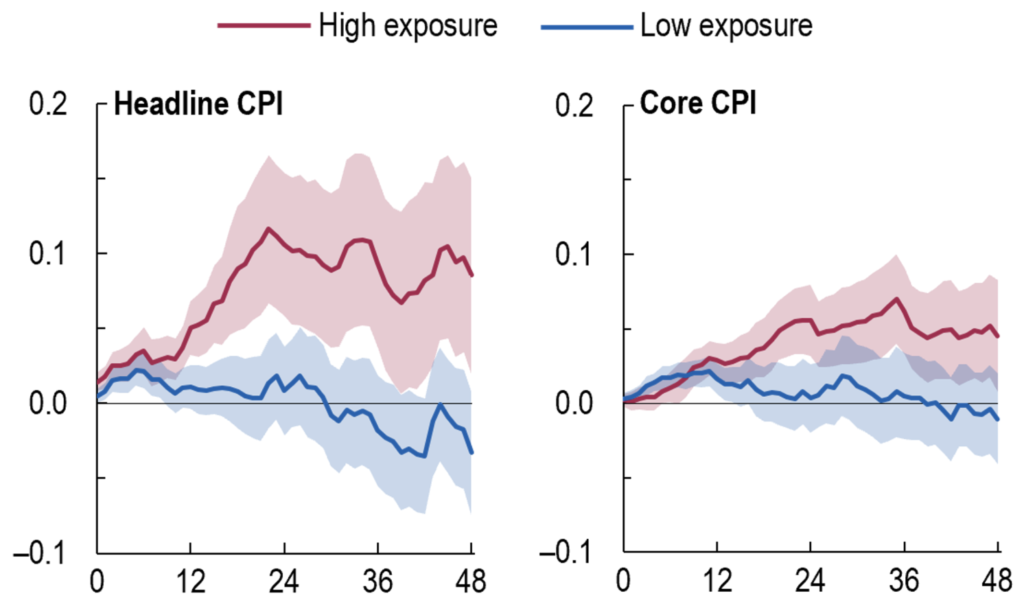

Figure 2 shows the average response of headline CPI inflation (left) and core CPI inflation (right), in cumulative terms, to a 1% increase in copper prices. Copper price shocks have significant effects on both headline and core inflation. A 10% increase in prices raises both headline and core inflation by about 0.2 percentage points within 12 months. Responses peak around two to three years after the shock, reaching 0.5 percentage points for headline and 0.3 percentage points for core inflation.

Figure 2 Impulse responses of inflation to copper supply shocks

Note: Cumulative impulse responses of headline CPI inflation (left) and core CPI inflation (right) to a one percent increase in copper prices (using the copper supply shock from Baumesiter et al. (2024) as an instrument). The x-axis denotes months after the shock. Shaded areas are 90% confidence bands based on cluster-robust standard errors.

Heterogenous responses to metals shocks: The role of production networks

To gauge the effect of metals price shocks on countries’ inflation through the domestic production network we use the small open economy model in Silva (2023). This model is amenable for our purposes as it clearly separates the effects of domestic productivity shocks to the metals sector from shocks to the international price of imported metals on inflation, which is what we study here.

Hence, we incorporate in our analysis an interaction term between copper prices and a country\’s network exposure to imported metals. Intuitively, countries with higher exposure to metals are countries that, directly and indirectly, use more base metals in the production of their goods and services. Therefore, an increase in base metal prices, increases the marginal costs of production for several sectors, which then translates downstream into higher producer prices and, eventually, higher CPI inflation.

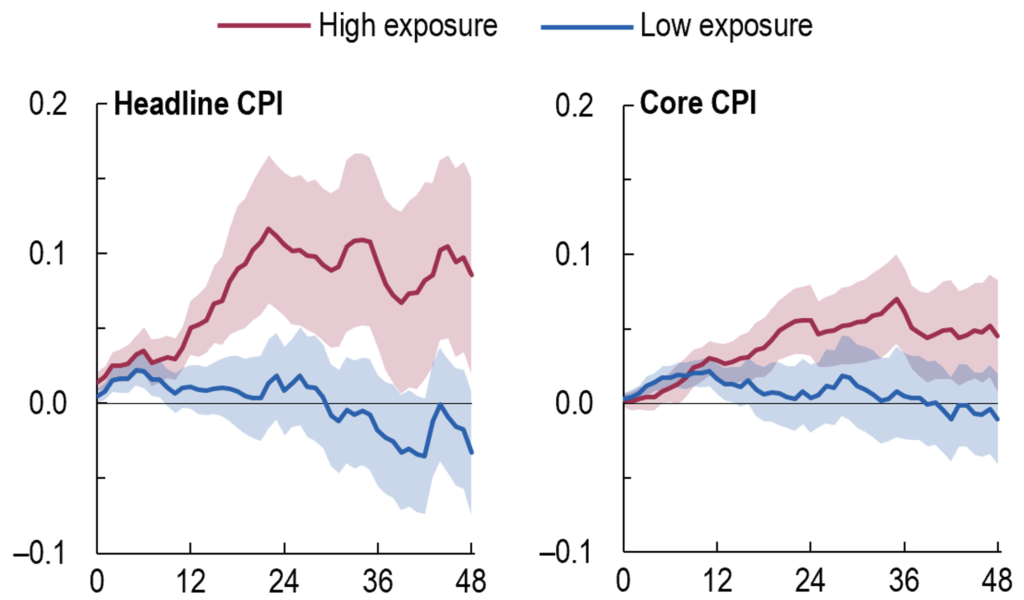

We evaluate the impact of copper supply shocks on countries with a metal exposure at the 90th and 10th percentiles of our sample – that is, a metal exposure of 0.008 and 0.002, respectively. Figure 3 shows the results. The effect of a copper price increase is significantly larger for countries with high metal exposure. The 12-month cumulative effect of a 1% increase in copper prices leads to positive effects of 0.05 and 0.03 percentage points on headline and core inflation, respectively. For countries with low network exposure, the effect is 0.01 and 0.02 percentage points, respectively.

Figure 3 Impulse responses of inflation to copper supply shocks: Countries with high metals exposure versus low metals exposure

Note: Cumulative impulse responses of headline CPI inflation (left) and core CPI inflation (right) to a one percent increase in copper prices (using the copper supply shock from Baumesiter et al. (2024) as an instrument). Red/Blue line denotes base metal exposure at the 90th/10th percentile of the sample in 2018, based on Silva (2023). Shaded areas are 90% confidence bands. The x-axis denotes months after the shock.

Finally, in our last empirical exercises we compare the inflationary effect of copper price shocks with the inflationary effect of oil price shocks. First, a 1% increase in oil prices due to a supply shock has a substantial impact on headline inflation, peaking at 0.07 percentage points after two to three years, but they have no significant effect on core inflation. Second, there is no significant heterogeneity in the impact based on oil exposure levels. Third, the impact on headline inflation diminishes over the long term, in contrast to the highly persistent impact of metals on core inflation in high-exposure countries.

Conclusions

Primary metals are an important source for inflation due to their role as intermediate inputs for investment goods in the production network. Given how they enter in the production network, metals supply shocks can have significant, persistent effects on core and headline inflation. In contrast, oil supply shocks mostly impact headline inflation over the short run.

While shocks to oil supply affect only one commodity, supply shocks to metals markets are more dispersed. Supply shocks to each of the metals markets may not hit at the same time. This has made so far, the magnitude of supply shocks to the aggregate primary metals sector smaller than in the petroleum sector, helping to tame the impact on inflation.

One implication of our finding is that if the world economy became more metals intense due to the energy transition (e.g. IEA 2022, Boer et al. 2024), inflationary surprises could be more persistent. In addition, metals supply shocks could become more frequent or sizeable due to trade fragmentation (Alvarez et al. 2024).

Would this make the work of central bankers easier or more difficult? Central banks have typically looked through oil price shocks, provided these were not excessively large. As the energy system moves away from fossil fuels, however, this approach may not work well when facing major fluctuations in metals prices. The monetary authority may, thus, eventually need to react to metals supply shocks as these shocks have a more persistent effect on core inflation. Central banks need to be prepared for a potentially more metals intense global economy where metals price shocks will gain importance and their effects on inflation could be initially less visible but more persistent.

Source: cepr.org